Practicing Kindness

The Importance of Kindness and How It Can Be Practiced in Schools

The philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau once wrote, “What wisdom can you find that is greater than kindness?” Eleanor Roosevelt said, “The basis of all good human behavior is kindness." There are so many great things happening in our classrooms. Yet, it’s also a time of challenges as teachers are locked into curriculums and policies that may be difficult to navigate.

Kindness is difficult to practice in those times when patience has been strained and demands are many. But, it’s those very times when role modeling kindness is most impactful and meaningful. It’s when taking a deep breathe to carefully choose words will make the difference between bringing peace to a classroom or elevating tensions.

Kindness is a foundational social behavior that underpins healthy relationships, productive learning environments, and well-functioning communities. While children are often instructed to “be kind,” such directives assume a shared understanding that may not exist. For a child who has never had kindness explicitly identified, modeled, or named, the direction to be kind lacks clarity and meaning. Kindness, therefore, cannot be transmitted solely through verbal expectation; it must be demonstrated, contextualized, and made visible through consistent adult modeling and guided practice.

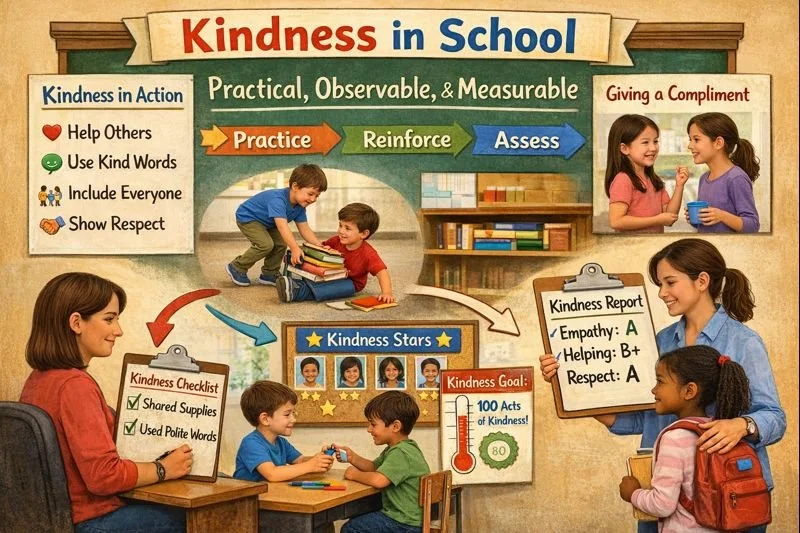

Within educational settings, kindness is not an abstract moral ideal but a practical and observable set of behaviors—listening respectfully, cooperating with peers, offering help, and responding with empathy—that can be explicitly taught, reinforced, and assessed. Peer-reviewed research supports this instructional approach. Durlak et al. (2011) found that school-based social and emotional learning programs, which include the direct teaching of kindness-related skills, produce statistically significant improvements in academic achievement, student engagement, and classroom behavior. As schools increasingly embrace their responsibility to educate the whole child, kindness has emerged not as an ancillary value, but as an essential and evidence-based component of effective pedagogy.Why Kindness Matters in Education

Peer-reviewed research shows that kindness-related prosocial behaviors among students significantly improve classroom social climate by strengthening peer acceptance, teacher–student relationships, and norms of cooperation and respect (Wentzel, 1998).

From a developmental perspective, kindness supports social competence. Children and adolescents who demonstrate kind behaviors—such as helping peers, listening respectfully, and showing consideration for others—are more likely to form positive relationships with classmates and adults. These relationships, in turn, are associated with higher engagement in school, improved attendance, and increased motivation to learn.

Research further underscores the importance of kindness. Acts of kindness activate neural pathways associated with reward, emotional regulation, and social bonding. Regular exposure to positive social interactions supports a child’s ability to manage impulse control, resulting in improved attention, problem-solving, and collaboration (Blair & Raver, 2015).

Kindness also serves a protective function within educational environments. Students who feel safe, valued, and respected are less likely to experience chronic stress, anxiety, or social isolation—factors that directly interfere with learning and healthy development. When kindness is embedded in school culture, it helps buffer the harmful effects of trauma, discrimination, and adversity, particularly for students from vulnerable or marginalized populations. This relationship is well supported by research and aligns with what educators and families observe in practice. The question, then, is not whether kindness matters, but how educators and parents—who are a child’s first teachers—can intentionally teach kindness as a learnable skill, translating an abstract value into consistent, observable behaviors (Jennings, 2009).

Kindness as a Teachable Skill

As in the teaching of reading and math, kindness can be intentionally integrated into curriculum and school routines.

Practicing kindness in all interactions does not require abandoning academic rigor. Instead, it complements academic instruction by creating conditions in which learning can flourish. When adults demonstrate how to treat others respectfully, through modeling, children learn how to resolve conflicts constructively and recognize the impact of their actions. With that, they are better equipped to participate productively in academic tasks. Yet, this is easier said than done. When you tell a child to “be kind,” what exactly does that mean? Are there levels of kindness? Degrees of kindness? Does it mean one thing to one person, or is the meaning universal? The word “kindness” is an abstraction, so to teach it, kindness must be demonstrated.

Instructional Strategies for Teaching Kindness

Purposeful Instruction

Kindness should be named, defined, and discussed. Lessons can focus on identifying kind behaviors, understanding emotions, and recognizing how actions affect others. Age-appropriate scenarios, role-playing, and guided discussions allow students to analyze social situations and practice appropriate responses.

Modeling by Adults

Teachers and staff play a critical role in demonstrating kindness. How adults speak to students, manage conflict, and respond to mistakes sets behavioral norms. Consistent modeling reinforces the idea that kindness is expected and valued.

Integration into Academic Content

Kindness can be embedded into core subjects. In literature, students can analyze characters’ actions and motivations. In social studies, discussions of historical events can include examination of cooperation, justice, and human dignity. Group work in science or mathematics provides opportunities to practice respectful collaboration and shared responsibility.

Classroom Routines and Norms

Daily routines reinforce kindness through predictable expectations. Morning meetings, class agreements, and reflection activities help establish a shared understanding of respectful behavior. Recognizing kind actions—through verbal acknowledgment or structured systems—reinforces positive conduct without relying on punitive discipline. When I taught 5th grade, our daily routine started and ended with a group meeting sitting on and around a couch placed in one of the learning center areas. We would go over the day’s tasks and events, such as an upcoming school assembly or music class, talk about what needed to be accomplished, and discussed any problems that had arisen, such as disagreements at recess. We worked out the problems as a group, not through punishment, but through discussion on how to manage conflicts with respect and garner the courage needed to be kind. And, it worked. The class functioned as a collaborative unit.

I used the same approach when working with chronic truants who lacked enough credits to graduate from high school. They truly disliked school, not because they weren’t interested in learning, but because school personnel had stopped listening to them years back and instead treated them through suspensions. The result was that they just stopped coming to school as soon as they had the resource to do just that - a car. If they came late to class, rather than grill them on why they were late, I just said, “I’m glad to see you. Where did you leave off yesterday so we can get you started on today’s work.” You would think that would give license to be late again, but the opposite happened. Kindness yields great dividends.

Peer Interaction and Cooperative Learning

Structured cooperative learning encourages students to work interdependently. Assigning roles, teaching communication skills, and reflecting on group processes help students practice kindness in authentic contexts. The high school students I worked with in the district’s alternative education program met off campus. I had a playpen so babies could be brought to class. No desks. Just a large table that served as a group workspace. When babies needed holding and moms were taking practice tests, another student simply took on the task of holding the baby. The space functioned as a family, and for some the first time they were part of a functioning family. At its core was kindness. Once again, I really did not know why things worked so well, why the students were showing up for school and passing their GED tests. I just knew whatever was happening worked. Looking back, I realize that the secret sauce was simply Kindness 101.

School-wide Approaches to Kindness

Effective kindness education extends beyond individual classrooms. School-wide initiatives create consistent expectations and shared language. It’s all about a culture of kindness, where words matter. It’s the discipline to stop before speaking, and it’s not all that easy when confronted by the minute by minute challenges ever-present in every classroom. But, developing a culture of kindness works.

Many schools adopt positive behavior frameworks such as Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS), which emphasize teaching expected behaviors, reinforcing positive actions, and using data to guide interventions. Kindness-related behaviors—such as helping others, inclusive language, and conflict resolution—can be explicitly taught and monitored within these systems.

Service-learning programs also promote kindness by connecting students with community needs. By participating in age-appropriate service projects, students learn empathy, civic responsibility, and the real-world impact of compassionate action.

Anti-bullying initiatives are another critical component. Programs that focus solely on punishment are less effective than those that teach empathy, bystander intervention, and respectful communication. A proactive emphasis on kindness reduces the conditions under which bullying occurs.

The Role of Families and Communities

Kindness education is most effective when reinforced beyond school walls. Schools that engage families through communication, workshops, and shared resources create continuity between home and school expectations. Simple strategies—such as shared language around respect and empathy—strengthen students’ ability to generalize kind behaviors across settings.

Community partnerships further reinforce kindness as a social value. Collaborations with local organizations, mentoring programs, and service agencies demonstrate that kindness is relevant beyond the classroom and contributes to broader civic life.

Measuring and Sustaining Kindness Initiatives

While kindness is a social behavior, it can be observed and assessed. Schools use a variety of indicators, including school climate surveys, behavioral data, attendance rates, and student self-reports, to evaluate the effectiveness of kindness-focused initiatives.

Sustainability requires ongoing professional development. Teachers benefit from training in social-emotional instruction, trauma-informed practices, and restorative approaches. Leadership commitment is also essential; when administrators prioritize servant leadership, kindness in policies, scheduling, and resource allocation, it becomes embedded in school culture rather than treated as a temporary program.

Final Thoughts

Kindness is a critical component of effective education. It supports academic learning, social development, and emotional well-being while contributing to safe and inclusive school environments. Far from being incidental, kindness can be systematically practiced through explicit instruction, modeling, integrated curriculum, and school-wide practices. When schools intentionally cultivate kindness, they equip students with skills that extend beyond academic achievement and prepare them for constructive participation in society.

**********************

References

Blair, C., & Raver, C. C. (2015).

School readiness and self-regulation: A developmental psychobiological approach. Annual Review of Psychology, 66, 711–731.

https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015221

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., & Schellinger, K. B. (2011).

The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions.

Child Development, 82(1), 405–432.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x

Jennings, P. A., & Greenberg, M. T. (2009).

The prosocial classroom: Teacher social and emotional competence in relation to student and classroom outcomes.

Review of Educational Research, 79(1), 491–525.

https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654308325693

Wentzel, K. R. (1998).

Social relationships and motivation in middle school: The role of parents, teachers, and peers.

Journal of Educational Psychology, 90(2), 202–209.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.90.2.202

Images generated by ChatGPT.